TENT MATERIALS

As you try to understand outdoor gear’s performance, you’ll notice it’s hard to wade through all the hyperbolic marketing. Naturally, every company wants you to think their materials are excellent and without flaw, but that results in grand but vague descriptions (e.g., “super light,” “stormproof,” “bomber”) where every company claims to have the best materials and made "no compromises". Advantages get touted while weaknesses go unmentioned.

That’s understandable – but problematic if you’re really trying to find the best gear. So rather than just claiming to be the best, we'll provide a deeper dive into our tent materials to explain their advantages, tradeoffs, and limits.

Our 15D polyester fabric

Intro

Our tents have been leaders in the modern resurgance of polyester in lightweight tents. We were not the first to use lightweight polyester, but our passionate advocacy for it combined with the popularity and benefits of our tents have been a key factors in its resurgence.

When the first X-Mid was introduced in 2018, we used polyester because we looked into its material characteristics and found differences in strength (compared to nylon) were not necessarily true or overstated, and polyester had key advantages of not absorbing nearly as much water so it doesn't swell up, expand, sag and dry slowly like nylon does. In our view, the sag of nylon when wet makes it highly problematic as a tent fly fabric because the sag results in a loss of structural rigidity (especially for a trekking pole tent, but freestanding nylon tents also weaken when the fabric sags). When we launched the X-Mid in polyester it was fairly new and many other tent companies were skeptical about its potential but it has since solidly proved itself with over a million user nights in our tents with a great track record and now a long list of previously skeptical companies following our lead to polyester.

While polyester is now widely viewed as a better material for ultralight tents and not nearly as controversial as it used to be, it is still worth taking the time to explain the advantages of polyester and the rest of the materials choices we use in our tents. As you might expect, our materials choices are reasoned from first principles to deliver the highest all-around performance. That’s not to say there aren’t compromises, though – the lightest fabric will never be the most durable.

Polyester vs Nylon

First, we need to be clear that debating the strength of polyester vs nylon is a big oversimplification because there are a huge list of variables that go into making a fabric that can be similar or more impactful than the fiber type. These include weave type, threadcount, calendaring, denier, heat treatments, coating thickness, coating type etc. As a result, the strength of fabrics can not be accurately estimated just from a few pieces of information like the fiber type and denier. Some polyesters are very weak, others are awesome. Some coatings increase strength, other coatings can seriously weaken a fabric. We strongly advocate for polyester as the better fiber, while also cautioning against assuming things about individual fabrics based on a few specs (not all polyester is good).

Now, the traditional argument for nylon is that it is the stronger fiber (especially in the nylon 6,6 chemistry version) and thus a nylon fabric can be made lighter for the same strength. Some companies will claim 50% or 100% higher strength for nylon. The counter argument for polyester is that these strength differences are quite overstated (when standardizing all the other factors like coatings), are even less in wet conditions, don't consider that that the sag of nylon increases stresses on a tent, and ignores that polyester has major advantages in water weight gain, drying times, and non-sag. More specifically, the problem with nylon is that it is a “hydrophilic” (water-loving) molecule, so when you camp in wet conditions, it absorbs water and swells up. That makes it heavy (it can gain 100% of its weight in water), slow to dry (since the water is in the fibers), and weaker by about 10% (since the swelling process stretches the molecular bonds). Thus, its strength:weight in rainy or even humid conditions is lower than its lab specification. You can read more about those hydrophilic chemical properties here. A related and more important problem is that in wet conditions nylon expands by 2-4%, which is why most tents look limp after rain and with the now saggy fly commonly stuck to the inner tent. 2-4% expansion may not sound like much, but it can be 6″ of slack over the arch of a tent.

Water absorption means that any strength advantage nylon has over a high quality polyester can disappear in wet/stormy conditions (where you most need that strength) because it gives up 10% strength while potentially doubling in weight. When you set up a nylon tent, it might be 10% stronger for the same weight, but once the rain starts, there’s little strength advantage yet you’re carrying around a heavier shelter.

What about poly? It is hydrophobic (repels water) and thus does none of that. In wet stormy conditions, poly remains strong, light, fast-drying, and retains an excellent taut pitch—outstanding qualities for tent fabric. Even if nylon had a sustained 15% strength advantage, the no-sag and fast dry characteristics of poly would be worth it. To conclude, polyester offers you similar strength, no sag performance, and fast dry while nylon offers an initial advantage in strength that roughly disappears when it rains, leaving you with a saggy, slow drying, and heavier tent.

The obvious conclusion here is that nylon is not well suited to tents – so why is it popular? After poly and nylon were invented in world war II, most tents did use polyester. With the movement to lighter tents in the ’80s, backpacking tents switched to nylon simply because only nylon was available in lighter weight versions (due to demand from other industries with more sway than the small tent industry). Meanwhile, poly remained only available in heavyweight versions and thus relegated to use solely in heavier mountaineering and car camping tents. In the last decade that has finally changed with lightweight poly now commercially available and proliferating. Thus, lightweight tents are switching to polyester with more brands making the switch each year.

Denier

Denier (or "D") is a strange unit that tells us the thread size. The actual units are strange: denier is the weight in grams for 9 km of thread.

What is more helpful is know the context. The very lightest woven fabrics are 4-5D like a superlight down jacket or windshirt. The lightest tent fabrics are 7D which is occasionally used on superlight tents intended for fair weather conditions. Three season tents used to be 70D a few decades ago but quickly went lighter to 30D and then over the past 20 years we've seen them settling in the range of 10-30D.

In our tents we use 15-20D woven fabrics which are fairly normal for a lightweight tent. We originally used 20D polyester for most of our tents and floors, but for 2025 we have introduced a high strength 15D polyester that offers almost identical strength (96% as strong) while being lighter. We also use 15D nylon in some of our tent floors where the differences between nylon and poly are less consequential.

We choose our fabrics based on being as light as possible while still being a well-rounded choice that is reliable in tough conditions. There is always a trade off between strength and weight, but we minimize that with high tenacity fabrics and choose fabrics that are durable enough to last a very long life when they are treated responsibly.

Coatings

Coating are important for both the waterproofness and strength of a fabric, but also are quite complicated as there are a wide range of chemistries, application processes, treatments, and thicknesses. Thus we can provide some general information but it doesn't necessarily apply to every fabric.

The traditional way of coating tent fabrics is with a PU (polyester urethane) coating, which is problematic stuff. It substantially weakens the material and slowly breaks down from water. Worse, it absorbs water inside so it can feels dry when it’s not (much like nylon). Thus, many tents have been ruined when people think they have them dried and store them away but the remaining moisture breaks down the fabric.

A much better coating is silicone. It’s solidly waterproof (when applied heavily enough) while actually strengthening the fabric instead of weakening it, plus being largely immune to degradation. It’s way better than traditional PU but still has a couple of downsides: you can’t seam tape it, and it’s so slick that tent floors become awkwardly slippery (especially if you’re camped on a slope).

More recently, a new formulation of PU has come along called polyether (vs. ester) urethane that doesn’t add as much strength as silicone but doesn’t lose as much as traditional PU either, and it solves both the degradation issues of conventional PU and the downsides of silicone (slippery, unable to seam tape). Confusingly, this coating is sometimes still called PU but is also called PE and PEU. The name is similar but the chemistry is much better than older PU, which is why most tent companies have made the switch. Almost all premium tents now use PE rather than PU, even if they say PU.

With our tents, we use dual coatings where the primary coating is a heavy coat of silicone on the outside for high waterproofness and additional strength. Then we also apply a thinner coat of PEU on the inside to add even more waterproofness and so we can seam tape it for you while giving a non-slippery floor. This avoids the potentially messy and tedious process of user seam sealing that can be unsightly and adds 20-50g to your tent.

Some companies will tell you that using silicone on both sides (called "sil/sil") is even stronger yet and often that it is true, but also this is one factor out of a long list of factors that affect strength so it does not necessarily mean one fabric is stronger than another because one is sil/sil and the other is sil/PEU. Fabrics of both coating types can range from excellent to poor. With our fabric we have access the latest formulations, so our sil/PEU polyesters are among the stronger polyesters on the market for their weight. We are proud of our 15D and 20D sil/PEU polyester fabrics because they offer excellent strength while having practical real world advantages in providing you a seam taped tent.

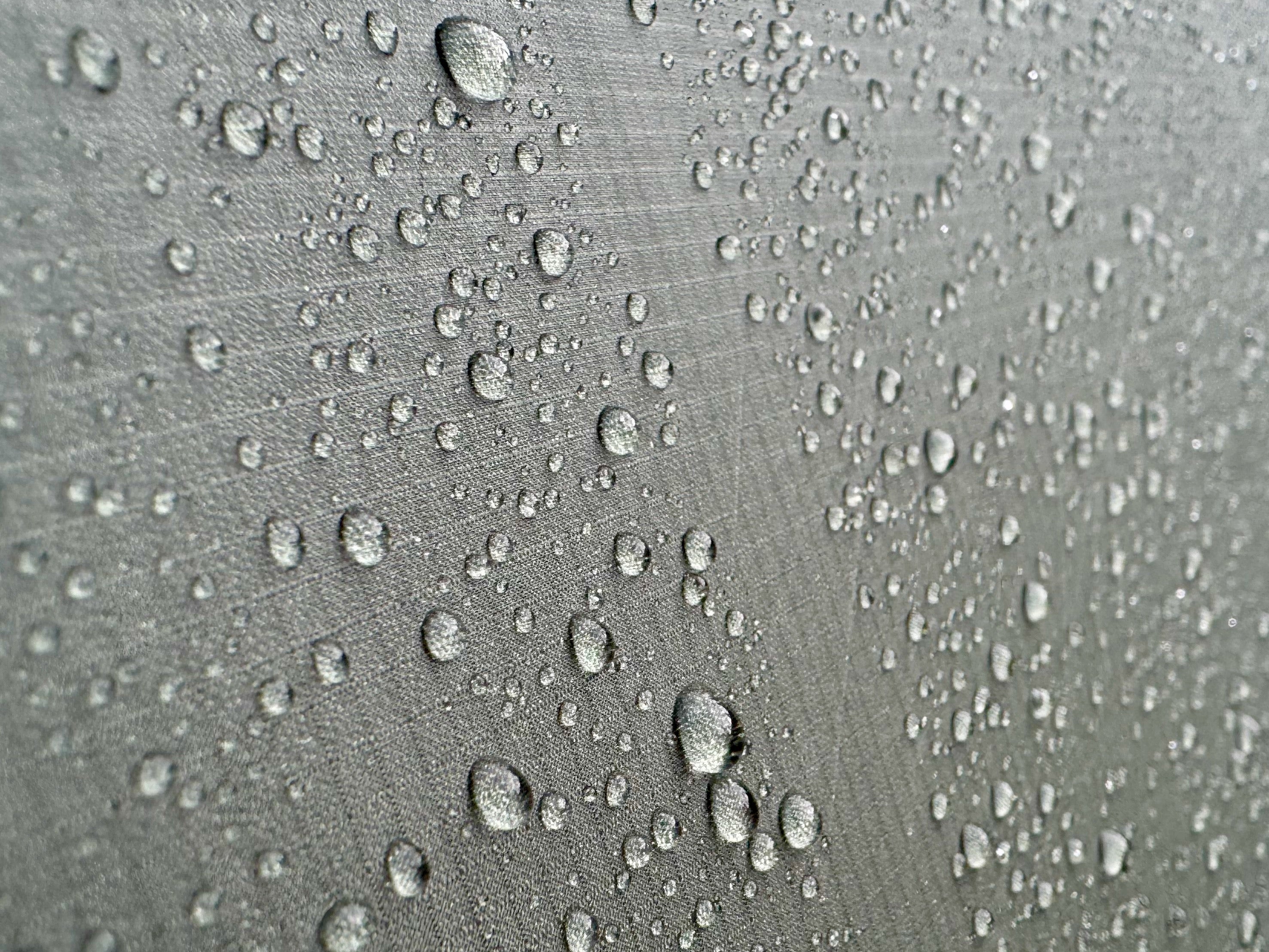

Waterproofness

All of that ignores the most crucial coating related topic: is it waterproof? The industry-standard approach here is to provide an HH specification for the new fabric, which tells you how much water you’d have to stack onto the fabric to get enough pressure to push it through. Unfortunately, these new specifications are almost useless because it ignores wear/degradation. Almost all coated fabrics are waterproof enough when new but then degrade such that a high initial HH might not translate to waterproofness later on. The key question is not how waterproof the fabric is at first, but how well it holds up over time.

The background here is that traditional PU degrades fairly quickly (as a generalization) to often leak, causing customers to ask for even higher initial HH like 5,000mm or even 10,000mm. Manufacturers oblige but thickening the PU lowers tear strength even more. What campers really need is not higher HH but rather less degradation. Sil/PU and PEU coatings can also wear down quickly if they are not well impregnated into the fabric. All coatings degrade a surprising amount, where the key is to keep them above ~600mm for as long as possible because real-world leaking happens at about 600mm in heavy rain.

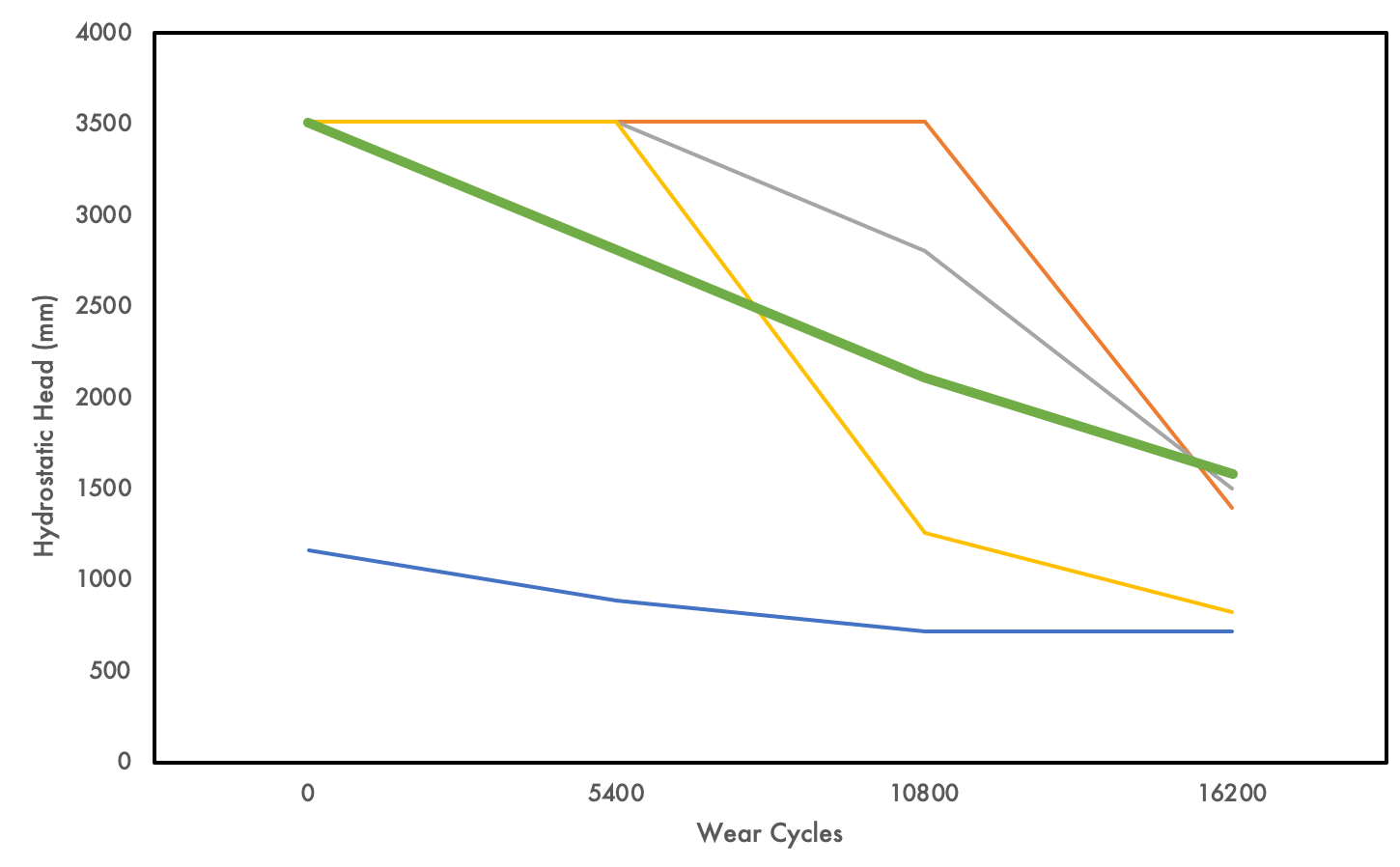

Below is a chart showing the hydrostatic head of the X-Mid’s fabric (green) as it is subjected to wear cycles compared to 4 other materials from other tent companies from independent lab testing:

You’ll notice all but one of these fabrics start at 3,500 mm – that isn’t the real maximum for these fabrics but just the upper limit of the testing equipment. The key takeaway from this chart is that the X-Mid fabric isn’t as high as some fabrics early on (e.g., 5,400 wear cycles), but because the coatings are well impregnated, it holds that waterproofing for longer. By the end (16,200 wear cycles), it is the most waterproof fabric (Note: 16,200 wear cycles roughly corresponds to many months of continuous high winds and heavy rain) and far above the 600 mm minimum. That performance at the end is what matters. Like tear strength, the goal isn’t to boast the highest new spec but rather avoiding dropping too low later in the tent’s lifespan.

Here we see the X-Mid fabric is on track to do that for longer than any of these competitors. The grey and orange fabrics perform well too, but the blue and yellow are problematic. Of all these fabrics, the X-Mid fabric shows the most gentle decline because the coatings are so well impregnated. At 1,600 mm after 16,200 cycles, it is on track to remain waterproof for the longest time and could likely repeat the entire test again while staying above 600 mm.

Find out about new gear + download Dan's ultralight gearlist: